My wife is doing some work

on one of the fathers of modern Art Therapy, Hans Prinzhorn, who worked with

patients in the psychiatric hospital of Heidelberg University in the 1920s and

early 1930s. After his death, the Nazis murdered many of the artists but also included

some of the art in an extraordinary exhibition – Entartete Kunst – Degenerate

Art.

The Picasso Museum in

Paris is currently hosting an exhibition of the same name, collecting together art

that survived the Nazi attack on this so-called degenerate culture and telling

the story of the Nazis’ relationship with Entartete Kunst. Josephine wanted to

go, she invited me to go with her. I enjoy hanging out with my wife.

The exhibition is, I think,

one of the most stunning and important I’ve ever seen. Partly because of the

way it tells a story about what happened then, but principally because of what

it tells us about what’s happening now.

Hitler, as we probably

know, fancied himself as an artist. He wasn’t a good artist, he was rejected by

the academy of Fine Arts in Vienna twice. And he never forgave … well millions

of people. And by the time he’s become Chancellor of Germany – and it’s worth

remembering he was indeed elected Chancellor of Germany in a democratic

election – he’s prepared to take his revenge. And art and artists were

denigrated, banished, destroyed, exiled and murdered. And in July 1937, the

Nazis opened Entatete Kunst – more than 700 works were shown on walls painted

with hate-filled slogans, “Revelation of the Jewish Racial Soul” or “Deliberate

Sabotage of the Armed Forces.” 4 million people visited – it’s staggering

really to imagine and amazing to see the grainy footage screened on the walls

of the Paris exhibition of crowds of well-to-do German housewives and Nazi high

officials wandering round the gallery.

The list of artists whose

work was exhibited is a roll call of the greatest artists of the time. There

were Jews – for Jews were among the greatest artists of the time – and the

Nazis certainly saw the Jews as degenerate.

There was Chagall – this

was included in the exhibition – it’s called The Pinch of Snuff or sometimes

The Rabbi of Vitebsk and was acquired by the Kunsthalle in Mannheim – the Nazis

dragged the art and the artist through the streets with a message attached

saying, “Taxpayer, you should know how your money was spent.” I knew the art –

I just, until I saw it on the wall this week, realised quite how large and

powerful a piece it was.

There was Oskar

Kokoshchka, whose work Alter Mann was exhibited – he lost his teaching position

at the Dresden Academy in 1933 and fled to Prague and then Great Britain. In

1943, he became president of the Free German Legue of Culture, the organisation

founded by Anti-Nazi cultural figures in exile.

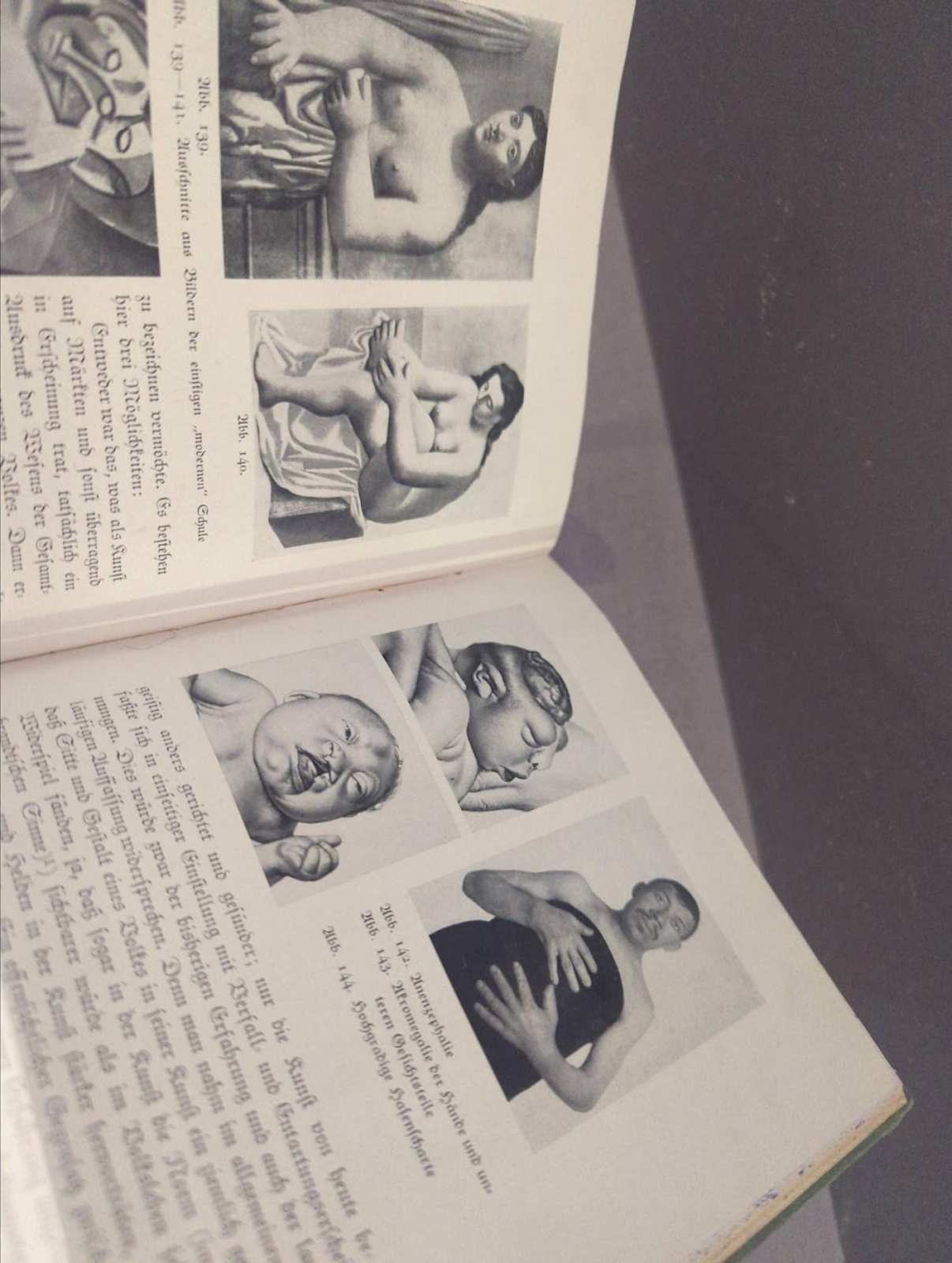

But it wasn’t just the

Jewish artists who were held to be degenerate. This is Picasso’s Seated Nude.

This wasn’t in the original exhibition – it was looted by the Nazis in 1940

from the collection of the Parisian Jewish art dealer, Paul Rosenberg. But the

photo of this piece was used in the book, “Art & Race” by the Nazi Paul

Schultze-Naumburg and ridiculed – it was shown alongside photos of the disabled

as a way of … what exactly, sneering and creating a kind of guilt-by-throwing-nastiness.

And then there were the

cubists – degenerate.

And the fauvists –

degenerate.

And the artists who like

colour or abstraction or …

This one broke my heart a

little.

This is Ernst Barlach – it

looked to me like a weeping angel. It was exhibited, in the contemporary

exhibition under a quote from its sculptor that read, “These times don’t agree

with me, I’m not to its liking, I’m not all decked out in the nationalist fashion,

my mode is unracist, noise frightens me, instead of cheering when the “Heil”

sounds roar, instead of making arm gestures in the Roman style, I draw my hat

down over my brow.”

Barlach’s degeneracy, it

seems, is being too soft, to able to experience and present through art pain

and loss – degenerate by Nazi standards indeed. I stood infront of this statue

and this quote and I cried.

It turns out that to the

Nazis, it wasn’t just the Jewishness of the artist, it was the richness of the

use of colour, or line or shape, or sense of fun or – and this is the real

point – the sense of an artist being an artist.

For the point of art to

express that which cannot be otherwise expressed.

I remember Tracey Emin

being interviewed and asked to explain her work.

“I can’t really,” she

said, “because if I could have explained it, I wouldn’t have had to have made

it.”

Art exists to say things

that cannot be controlled or even expressed using what we already know. Art

exists to say the things that we don’t know yet, to open up the possibility of,

to those who see the art and are moved by the art, to experience something we

don’t already know. Great art – and my, I saw some great art in Paris this week

- makes us realise things we somehow

instinctively know are true, even we could never have expressed that truth

before now – before the very moment of seeing and feeling the art in our soul.

Art doesn’t fit. To create

art is to commit to a kind of iconoclasm – that word that literally means a

breaking of idols. And when as a dictatorial fascist regime, a government – and

I’m not just thinking of the Nazi government – demands that artists fit a

pre-realised sense of what truth is, that will always fail.

And even if that

dictatorial fascist regime destroys art and the first gallery in the exhibition

contains half destroyed pieces of Degenerate Art – the art survives, the ideas

survive.

And thank God they do.

Because if we just had the

things we already understood – or thought we already understood – if we just

had the science we understood at any given moment, we wouldn’t have a hope as

human beings. We’d be stuck never growing, never developing. We would never

have made it beyond smashing rocks together. It’s the art, it’s the iconoclasm

that opens up the possibility of growth, of learning, of realising the things

today we didn’t understand yesterday and realising too that there are new

things to learn tomorrow.

It's artists who

understand, perhaps better than us normal human beings the importance of that

line from Sameul Beckett’s Waiting for Godot – “Ever tried? Ever failed?

No matter. Try again, fail again, fail better.”

I think that’s why art and

artists so distress the dictators and the fascists and the autocrats. Because

they like things the way they are – when they are in power. And they don’t want

to look beyond the things they know already. They don’t like being told they

are failing.

That’s why, for what it’s

worth, Jews no longer offer sacrifices. Because we are artists in our religious

soul. And as much as there was beauty in that observance then, times changed

and we changed and there was creativity and bravery and there arose from the

rubble of the destroyed Second Temple a new idea even more beautiful than

sacrifices – and certainly less bloody.

That’s why, for what it’s

worth, New London was founded, because Rabbi Louis Jacobs just couldn’t bring

himself to tow a party line of acceptable tings that acceptable Orthodox Rabbis

were supposed to say. He wanted to say

the right thing, the thing that felt perhaps uncomfortable, made people feel

uneasy. He wanted to speak truth. I think Louis Jacobs, if he had been to Paris

to see this remarkable exhibition would have been proud to consider himself one

of the degenerates.

I think we should all be

proud to consider ourselves degenerates.

For, in truth, we are all

degenerate in our way. Artists of our own lives, trying failing, trying again,

failing again, failing better. All of us, a little too tall, or a little too

short or a little too fond of bright colours or pastel colours of sharp lines

or hazy lines or … in our idiosyncrasy and perfect individuality – we disturb

and disrupt this awful notion that seems to powerful and so dangerous in our

time and in the 1930s too – that we should all subscribe to some kind of

prescribed appropriateness. Vive la difference.

Salute the bravery of

those once did, and continue to, stand up to autocracy and fascism.

Salute the bravery of

those who once did, and continue to, seek to try again, fail again and fail

better.

Salute the incredible

diversity of humanity in all of its forms and in its creativity most especially.

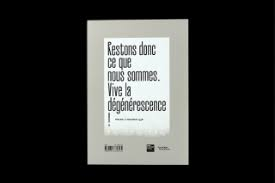

As Otto Dix, another of the great artists oppressed by the and exhibited in 1937 in Munichg and today in the Picasso Museum in Paris, as Otto Dix said,

Restons donc ce queue nous sommes. Vive la degeneresence.

Let's be that which we are. Long live degenerecy.

Shabbat Shalom