I bought a new siddur. It’s not that I don’t have enough,

but this one is very, very special. My dear colleague, Rabbi Adam Zagoria

Moffet – together with Isaac Treuherz, has just published Siddur Masorti – the

first-ever Hebrew-English, egalitarian, fully-transliterated, Sephardi (phew!) Siddur.

Looking at it feels like looking at the future, or rather it makes every other

Siddur on my groaning shelves look distinctly passé.

The first thing that strikes is the beauty. It’s a labour of

love executed with tremendous graphic style. The Hebrew layout is driven by meaning

and the dynamic of prayer; central terms dominate, poetry breathes as it

cascades down the page. You can feel rhythms and watch rhymes. Colour becomes a

hypertext, the main text is black, but the appearance of orange on the page, in

both the Hebrew and English, links to a commentary – and the commentaries are

precise, insightful and steeped in learning.

Hebrew appears on the left of the page, English on the right

– it’s a shift from the Siddurim of my youth, but a much better way to

appreciate the relationship between the two languages with the eyes able to move

from the centre of a spread to the outside with more ease. (I think Reb Zalman –

who would have loved this Siddur – pioneered that idea). The rubrics (bowing,

standing and the like) are displayed on the page with a style so classy, it’s almost

witty. It’s really very impressive.

Alongside the Hebrew and the English is a full

transliteration, following a formal academic convention. That’s befitting for a

Sephardi project (the Sephardim are known for their passion for grammar). I’ve

never seriously engaged with these conventions before, but I have a whole new

appreciation for how these technical elements allow similar-sounding Hebrew

letters and vowels (including the Shva) to be so clearly differentiated – it’s

a transliteration that honours Hebrew, and, I think, will draw non-Hebrew readers

into a closer relationship with the language of our faith.

Then there is the translation; in particular the translation

of God. The Tetragrammaton is … simply not translated, rather the Hebrew

letters appear in the midst of the English, beggaring our ability to express the

inexpressible. It’s a decision that makes the androcentric ‘LORD’ used in the 2006

Sacks Siddur feel very clunky. And when it comes to pronouns for God, Rabbi

Adam uses ‘They, Their, Them etc.’ In an introductory note, he acknowledges that

that decision will appear ‘odd or even potentially heretical,’ but argues

persuasively (to me at least) that God is beyond the assumption of masculinity

that the English pronoun ‘he’ demands, but the Hebrew pronoun ‘Hu’ does not.

Then he shares this, “Hebrew has already introduced to us a plural noun for a

singular subject (and singular verbs) with the common divine appellation Elohim.”

It takes a while for someone steeped in Hebrew prayer to realise what this siddur

makes so explicit. The Hebrew word Elohim comes in the plural form, but –

when referring to the One God – is twinned with singular verbs. Hebrew has been

using a plural term to refer to the Singularity for centuries. The oddity of referring

to God in a phrase such as ‘They creates’ matches perfectly the oddity of the Hebrew

words that open the entire Torah, ‘Bara Elohim’ with its plural noun and singular

verb.

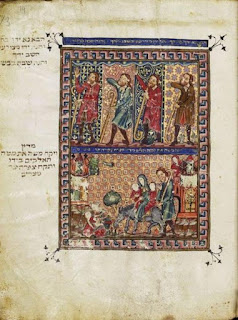

There’s more to say; about the appearance of Miriam and the matriarchs,

about call-up options for men, women and those who identify as non-binary, the

Ladino, the beautiful line drawings …. It really is very, very special. At

present Siddur Masorti only exists in a weekday edition. I know a Shabbat

version is, at the very least, under consideration. I’ll have a copy with me in

services in the coming weeks, and you can also read more, see sample pages and

order copies at http://siddurmasorti.com/.

Bravo Adam, proud to have you as a colleague.